Here are my notes, made after reading each book (here referred to as a chapter) and the sections contained within those books. These notes are not intended to replace reading the book, which is essential for a better understanding of the concepts, but rather aim to help readers review and complement their reading.

Some notes have been supplemented with my own observations and ideas. As the book’s author himself suggested, some sections and books are intended for a non-lay audience; such sections and books were skipped in these notes, which are primarily aimed at the lay reader.

The edition read was:

- Title: Antifragile – Things That Gain from Disorder

- Author: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Publisher: Objetiva

- Publication Year: 2020

- Edition: 1st edition

- Language: Portuguese

- Number of Pages: 616

- ISBN-13: 978-85-470-0108-7

- ISBN-10: 8547001085

Chapter 1: The Antifragile: An Introduction

1. Between Damocles and Hydra

Something that often goes unnoticed is the difference between being robust and being antifragile. But what is antifragile? It’s evolving through mistakes, being a Hydra—when one head is cut off, two grow back in its place. Being robust or resilient is good, but you don’t gain anything from adversity; you merely endure it. This concept is seen in various areas, such as medicine:

- Hormesis: A beneficial response to low doses of a poison.

- Mithridatization: The process of inducing resistance to a poison or toxin through the gradual administration of sub-lethal doses.

2. Overcompensation and Exaggerated Reactions Everywhere

- Overcompensation (Redundancy): When exposed to a stressor, an antifragile system doesn’t simply return to its original state—as a robust or resilient system would—but overreacts to become better and more capable of handling future stressors.

- Example: Post-traumatic growth; censoring something boosts its visibility; weightlifting; etc.

Be antifragile, not just robust or resilient!

3. The Cat and the Washing Machine

The cat (an organic system) is antifragile because it strengthens with stress and randomness—when startled, it becomes more alert—whereas a washing machine (a mechanical system) breaks under pressure.

Taleb criticizes the modern tendency to treat complex systems, like economies or the human body, as machines requiring rigid control, which increases their fragility.

A bit of randomness and discomfort is necessary! Antifragile systems shouldn’t be used to avoid mood swings but only to prevent catastrophic outcomes like suicide.

4. What Doesn’t Kill Me Makes Others Stronger.

The failure of one part can benefit the whole. When a fragile component collapses, it releases resources or eliminates inefficiencies, allowing the system to adapt and become more robust.

Example: A forest fire destroys individual trees but renews the ecosystem by clearing dead material and making space for new growth, preventing larger disasters in the future.

Risks = engines of renewal.

Chapter 2: Modernity and the Denial of Antifragility

5. The Souk and the Office Building

- Office Buildings: Fragile, centralized, and prone to catastrophic failures, such as terrorist attacks or power outages, due to their hierarchical structure.

- Souks: Represent decentralized systems with multiple access points and diffuse layouts, making them more adaptable and resistant to shocks, like localized damage.

- Intervention Bias: The modern tendency to create systems that, in trying to eliminate volatility and chaos, end up becoming more vulnerable to unexpected events.

6. Tell Them I Love (a Bit of) Randomness

Randomness can be a stabilizing force in certain systems. This contrasts with the common view that randomness is always disruptive.

Modernity seeks control and predictability, resulting in fragile systems vulnerable to unexpected collapses.

7. Naive Intervention

- Iatrogenics: Interventions, such as medical treatments or economic policies, that cause unintended harm while trying to “fix” systems.

- Over-intervention vs. Under-intervention: Excessive action in low-risk situations and inaction in real crises weaken systems.

- Complexity

- In Praise of Procrastination: Delaying decisions allows additional information to emerge, reducing impulsive and unnecessary interventions. This contrasts with the modern culture of immediate action.

- The signal is more important than the noise; more data doesn’t necessarily mean better science.

8. Prediction as a Fruit of Modernity

Making predictions has an iatrogenic effect. For Taleb, the predictive method itself is flawed. The focus should be on the robustness or antifragility of systems, not on forecasting future models. The ideal world isn’t one where we get all predictions right, but where prediction errors don’t cause harm due to the robustness built into systems.

Instead of predicting failure and the probabilities of disaster, we should focus on exposure to failure.

Chapter 3: A Non-Predictive Worldview

9. Fat Tony and the Fragilistas

Fat Tony thrives in environments of uncertainty and volatility, profiting by identifying and betting against fragile systems. In contrast, Taleb presents the “fragilistas”—typically academics and policymakers—who try to control the world through theories and predictions.

Antifragility isn’t based solely on planning or predictions but on the ability to act and adapt to uncertainty.

10. The Advantages and Disadvantages of Seneca

Seneca trained his mind to accept losses. He embraces the advantages of being wealthy and “ignores” the disadvantages, contrary to what many “stoics” preach today.

Barbell Strategy: Allocate the majority of resources (90%) to safe options and a small fraction (10%) to high-risk investments.

- “Fragility implies having more to lose than to gain, which equals more downside than upside, which equals unfavorable asymmetry.” (p. 185)

- “Antifragility implies having more to gain than to lose, which equals more upside than downside, which equals favorable asymmetry.” (p. 185)

11. Never Marry a Rock Star

Barbell Strategy: Extreme stability with calculated risks, avoiding the vulnerable middle ground.

Instead of marrying a rock star (something volatile and risky), opt for a secure base (marrying an accountant) and allow small exposures to risks (flirting with the rock star). This protects against severe losses while maintaining the chance for unexpected gains.

Mixing safe investments with risky ones, keeping a stable job while exploring side projects, breaking furniture and then being rational (Greeks), having conversations with taxi drivers and scholars, etc.

In short, avoid the middle ground!

Chapter 4: Optionality, Technology, and the Intelligence of Antifragility

12. Thales’ Sweet Grapes

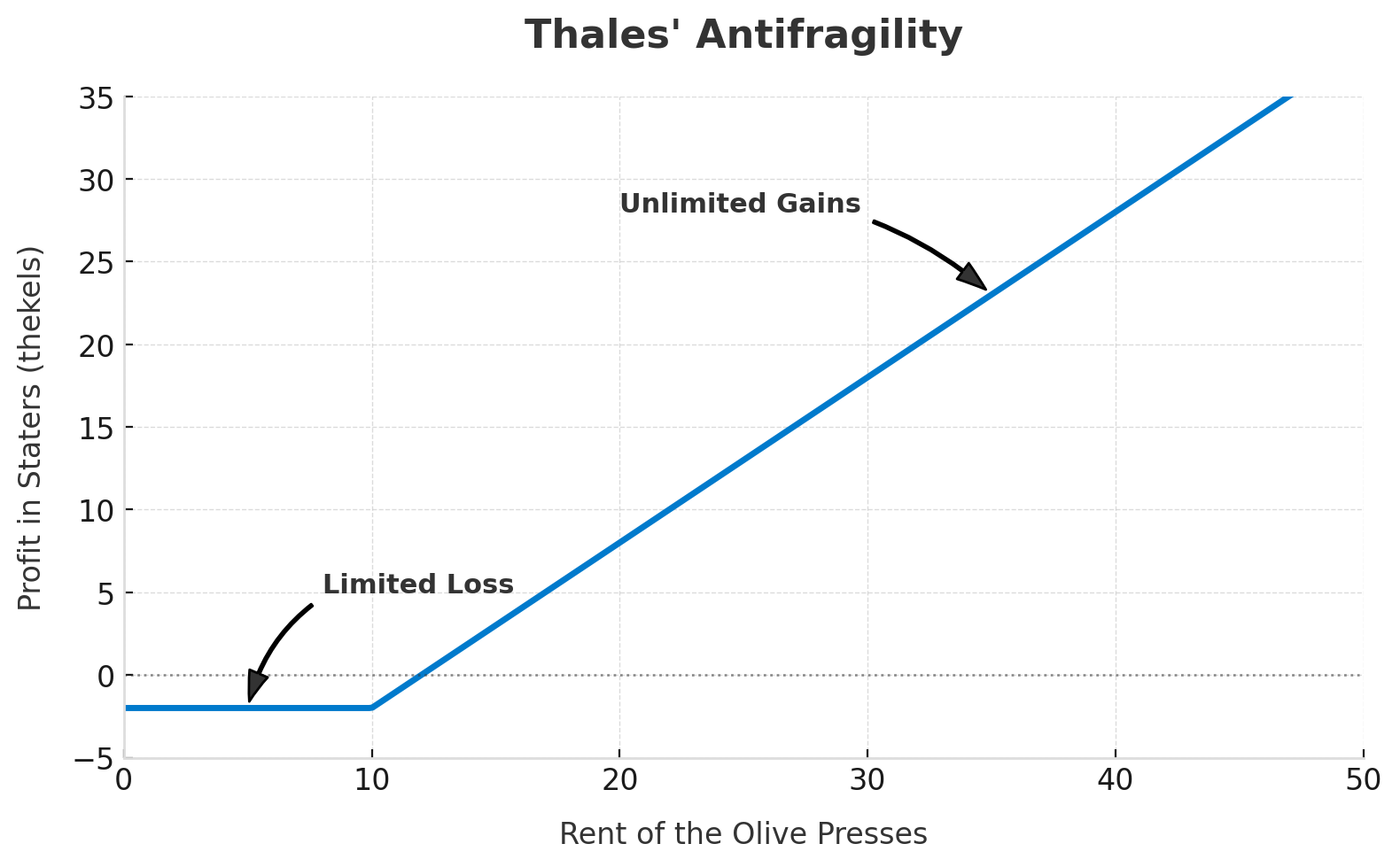

Thales placed small deposits to secure the exclusive right to use local olive presses during the harvest season. Option: “The right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell.”

Asymmetry:

- Bad Scenario: If the harvest was poor, he would lose only the small deposits paid for the options.

- Good Scenario: If the harvest was good, he would control the presses and could rent them out at high prices.

Optionality can be more valuable than traditional intelligence.

13. Teaching Birds to Fly

Imagine elderly professors, dressed in black togas, trying to teach birds to fly through technical lectures filled with jargon and complex equations. Birds don’t need theoretical lessons to learn to fly, just as many technological innovations don’t primarily arise from academic theory.

Random experimentation → Heuristics (technology) → practice and learning.

Instead of:

Academia → Applied Science and Technology → Practice

- “Causality is not correlation, and vice versa.” (epiphenomena)

- “The history of the wheel also illustrates the central point of this chapter: both governments and universities do little, very little, for innovation and discovery, precisely because, in addition to their blinding rationalism, they seek the complicated, the sensational, the noteworthy, the narrated, the scientistic, and the grandiose, rarely the small wheel on a suitcase. Simplicity, you see, doesn’t win medals.” (p. 221)

14. When Two Things Are Not the ‘Same Thing’

Knowledge we consider “essential” can be completely irrelevant to practical success.

Example: Joe Siegel and “green wood”; despite his success, he thought the wood was painted green.

Example 2: The world’s top expert in Swiss franc exchange rates doesn’t know where Switzerland is on a map.

Education doesn’t generate wealth but stems from it. It should be pursued for its own merits, not for economic gains. Innovations come from taking risks, not from research (theory vs. practice).

Talkers are terrible at explaining narratives but excel in practice. Academics are the opposite.

15. History Written by the Losers.

“We don’t put theories into practice. We create theories from practice.” Most errors that exist and were developed over time were “empirical developments, based on trial, error, and experimentation by skilled artisans trying to improve productivity and thus the profit of their factories.”

“Practitioners don’t write; they do. Birds fly, and those who lecture about them are the ones who write their history.” Most innovations arise unplanned and empirically.

16. A Lesson in Disorder

- Ecological Domain: Represents real learning, based on direct experience with reality.

- Ludic Domain: Represents artificial, controlled learning detached from reality.

Overprotective parenting results in fragility, not protection.

Study what interests you most, be self-taught, but value the boredom and difficulties to be overcome in studying and reading.

17. Fat Tony Debates Socrates

It’s not necessary to explain something to truly know it. The Socratic method “kills” functional knowledge through intimidating interrogations that make people feel foolish for following their instincts and traditions, without offering practical alternatives.

Chapter 5: The Nonlinear and the Nonlinear

This chapter was skipped, as noted in the footnote on page 305: “The lay reader can skip Book V without any loss: the definition of antifragility, based on Seneca’s asymmetry, is sufficient for a literary reading of the rest of the book. Here, it’s a more technical reformulation.”

18. On the Difference Between One Large Stone and a Thousand Pebbles

19. The Philosopher’s Stone and Its Inverse

Chapter 6: Via Negativa

20. Time and Fragility

-

Neomania: The unhealthy tendency to constantly seek the new, the modern, and the “progressive.”

-

Lindy Effect: For the perishable, each additional day in its life translates to a shorter additional life expectancy. For the non-perishable, each additional day may imply a longer life expectancy.

Non-perishable: Immaterial or replicable things without physical wear, such as ideas, books, theories, cultural practices, etc.

Perishable: Entities subject to wear, consumption, or physical obsolescence, such as food, living beings, manufactured objects, fuels, etc. -

Via Negativa: Removing harmful elements instead of always adding new components.

Example: Knowing what doesn’t work is more robust than knowing what works.

Example 2: Knowing what won’t exist in the future is more robust than knowing what will.

21. Medicine, Convexity, and Opacity

1. First Principle of Iatrogenics: Empiricism

- The natural doesn’t need to prove its efficacy, but the unnatural does.

- Medical intervention must be justified, not non-intervention. Avoid unnecessary treatments.

2. Nonlinearity

- The effects of medicine are nonlinear—the response is not proportional to the dose.

- Iatrogenics increases convexly (at an accelerating rate) as the severity of the condition decreases.

- Removing the harmful is more effective than adding treatment.

- Intervention only when the benefits significantly outweigh the risks (near-fatal: justifiable).

- Nature operates through opaque processes we don’t fully understand.

- Act as if we don’t have the full story.

- Sophistication requires accepting that we’re not as sophisticated as we think.

22. Living Long, But Not Too Long

Applying via negativa to health and longevity, advocating the subtraction of harmful elements like smoking, iatrogenic medical interventions, and excessive wealth to promote antifragility instead of superficial additions. Promote fasting, nutritional randomness, and acceptance of mortality.

Chapter 7: The Ethics of Fragility and Antifragility

23. Skin in the Game: Antifragility and Optionality at Others’ Expense

Don’t trust those who don’t risk their own skin: opinions without personal cost generate fragility for everyone.

24. Fitting Ethics to a Profession

Emphasizes that ethics should shape professions, similar to what was proposed by the Code of Hammurabi, i.e., “skin in the game.”

Criticizes “Big Data” for its excess noise and scarcity of signals. Above all, it proposes prioritizing antifragile systems that avoid convenient moral adaptations for personal gain, such as former public officials using their knowledge and experience at others’ expense in private companies.

25. Conclusion

“All things gain or lose from volatility. Fragility is what loses from volatility and uncertainty.”

Tables and Charts

The Triad: The fundamental distinction between the Fragile (which breaks with chaos), the Robust (which resists chaos), and the Antifragile (which benefits from chaos), using the metaphors of the Sword of Damocles and the Hydra.

Table 1: The Triad in Economics and Finance

| Domain | Fragile | Robust | Antifragile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business | Industry | Microenterprise | Artisan |

| Finance | Debt | Equity capital | Venture capital |

| Finance | Public debt | Public debt without bailouts | Absence of convertibles |

| Economic Life | Econofastro sects | Entrepreneurs | |

| Finance | Banks, hedge funds managed by econofastros | Hedge funds (some) | Hedge funds (some) |

| Companies | Efficiency, optimized | Redundancy | Degeneracy (functional redundancy) |

| Economic Life | Selling options | Family business | Buying options |

| Financial Dependence | Corporate employee, tantalized class | Dentist, dermatologist, niche worker, minimum-wage worker | Taxi driver, artisan, prostitute, f*** money |

| Options Trading | Selling volatility, gamma, vega | Uniform volatility | Buying volatility, “gamma,” “vega” |

Table 2: The Triad in Knowledge, Science, and Philosophy

| Domain | Fragile | Robust | Antifragile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thinkers | Plato, Aristotle, Averroes | Early Stoics, Menodotus of Nicomedia, Popper, Burke, Wittgenstein, John Gray | Roman Stoics, Nietzsche, Montaigne, young Silver, Hegel (Contradiction), Jaspers |

| Philosophy / Science | Rationalism | Empiricism | Skeptical empiricism, subtractive |

| Science / Technology | Directed research | Opportunistic research | Stochastic experimentation (antifragile experimentation or tinkering) |

| Science | Theory | Phenomenology | Heuristics, practical artifices |

| Ancient Culture (Nietzsche) | Apollonian | Dionysian | Balanced mix of Apollonian and Dionysian |

| Ethics | The weak | The magnificent | The strong |

| Knowledge | Explicit | Tacit | Tacit with convexity |

| Epistemology | True-false | Sucker-non-sucker | |

| Knowledge | Academia | Expertise | Erudition |

| Science | Evidence-based phenomenology |

Table 3: The Triad in Personal and Everyday Life

| Domain | Fragile | Robust | Antifragile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Well-being | Post-traumatic stress | Post-traumatic growth | |

| Human Body | Softening, atrophy, “aging,” sarcopenia | Mithridatization, recovery | Hormesis, hypertrophy |

| Food | Food corporations | Restaurants | |

| Physical Training | Organized sports, gym equipment | Barbell: parents’ library, street fights | |

| Medicine | Via positiva—additive treatment (prescribing medication) | Via negativa—subtractive treatment (eliminating consumption items, e.g., cigarettes, carbohydrates, etc.) | |

| Life and Thought | Tourist, personal and intellectual | Flâneur, with an immense personal library | |

| Human Relationships | Friendship | Kinship | Attraction |

| Characteristic | The Mechanical (Non-Complex) | The Organic (Complex) |

|---|---|---|

| Maintenance/Repair | Requires continuous repairs and maintenance | Self-repairing |

| Relationship with Randomness | Hates randomness | Loves randomness (small variations) |

| Recovery | No need for recovery | Requires recovery between stressors |

| Interdependence | Little or no interdependence | High degree of interdependence |

| Effect of Stressors | Stressors cause material fatigue | Absence of stressors causes atrophy |

| Aging | Ages with use (natural wear) | Ages with lack of use* |

| Reaction to Impacts | Undercompensates with impacts | Overcompensates with impacts |

| Effect of Time | Time brings only senescence | Time brings aging and senescence |

After reading this chapter, Frano Barović wrote to me: “Machines: use them or lose them. Organisms: use them or lose them.” Note also that everything that is alive needs stressors, but not all machines need to be left alone—an aspect we will address in our discussion of tempering.

Table 4: Fragilizing Interventionism and Its Effects

| Area of Knowledge | Example of Interventionism | Iatrogenics / Costs |

|---|---|---|

| Medicine, Health | Excessive treatment, constant feeding, thermal stability, etc., denying the randomness of the human body, addition rather than subtraction, dependence on medications | Fragility, medical errors, sicker (yet longer-living) people, richer pharmaceutical companies, antibiotic-resistant bacteria |

| Ecology | Micromanagement of forest fires | Increased total risks, “large fires” more destructive |

| Politics | Central planning, U.S. support for “engaged” regimes “in the name of stability” | Informational opacity, chaos after revolution |

| Economics | “No more boom-bust cycles” (Greenspan, USA); Labour (UK); Great Moderation (Bernanke); state interventionism; optimization; illusion of pricing rare events, Value at Risk methodologies, illusion of economies of scale, ignorance of second-order effects | Fragility, deeper crises when they occur, support for solid corporations allied with governments, stifling of entrepreneurs, vulnerability, pseudo-efficiency, large-scale explosions |

| Business | Positive advice (what to do), focus on returns rather than risks (what to avoid) | Richer charlatans, corporate bankruptcies |

| Urbanism | City planning | Urban decay, decaying urban areas, residential areas in city centers, depressions, crime |

| Forecasting | Forecasting in the Black Swan Domain (Fourth Quadrant) despite a terrible track record | Hidden risks (people take more risks when they have a forecast) |

| Literature | Editors trying to modify the author’s text | Blander writing, in the commoditized style of the New York Times |

| Child-Rearing | Helicopter parenting, eliminating all levels of randomness from children’s lives | Touristification of children’s minds |

| Education | The concept is entirely rooted in interventionism | Ludification—transformation of children’s brains |

| Technology | Neomania | Fragility, alienation, nerdification |

| Media | High-frequency sterile information | Breakdown of the noise/signal filtering mechanism, interventionism |

Table 5: Ethics and the Fundamental Asymmetry

| DO NOT RISK THEIR OWN SKIN (Keep the upside, transfer the downside to others, hold an ace up their sleeve at others’ expense) | RISK THEIR OWN SKIN (Keep their own downside, assume their own risk) | RISK THEIR OWN SKIN FOR OTHERS OR PUT THEIR SOUL IN THE GAME (Assume their own downside for the sake of others or universal values) |

|---|---|---|

| Bureaucrats | Citizens | Saints, knights, warriors, soldiers |

| Empty talk (“bullshit,” in Fat Tony’s dialect) | Actions, not bullshit | Costly conversations |

| Consultants, sophists | Merchants, entrepreneurs | Prophets, philosophers (in the pre-modern sense) |

| Business | Artisans | Artists, some artisans |

| Corporate executives (in suits and ties) | Entrepreneurs | Entrepreneurs / innovators |

| Theorists, data miners, observational studies | Lab and field experimenters | Independent scientists |

| Centralized government | City-state government | Municipal government |

| Editors | Writers | Great writers |

| Journalists who “analyze” and predict | Speculators | Journalists who take risks and expose frauds (powerful regimes, corporations) |

| Politicians | Activists | Rebels, dissidents, revolutionaries |

| Bankers | Traders | (Do not engage in vulgar commerce) |

| The fragilista Prof. Dr. Joseph Stiglitz | Fat Tony | Nero Tulip |

| Risk sellers | Taxpayers (put their soul in the game somewhat involuntarily, but are victims) |

Quotes I Highlighted During Reading:

“My idea was to be rigorous in the open market. This made me focus on what an intelligent anti-student needed to be: a self-taught person—or a person of knowledge, compared to the students called, in Lebanese dialect, ‘swallowers,’ those who ‘swallow school material’ and whose knowledge comes solely from the programming of courses. I realized that the difference wasn’t in the package of what was in the official bachelor’s curriculum—content that everyone mastered, with small variations that multiplied into large discrepancies in grades—but precisely in what was outside the curriculum.”

P. 283, Book IV

“Their strength [academics’ strength] is extremely domain-specific, and their domain doesn’t exist outside of ludic and well-organized constructs. Indeed, their strength, just like that of hyper-specialized athletes, is the result of a deformation. I thought the same applied to people selected for trying to get high grades in a small number of subjects rather than following their curiosity: try taking them slightly away from what they studied and watch their disintegration, their loss of confidence, and their contradictions. […] I’ve debated many economists who claim to be experts in risk and probability: when they stray slightly from their narrow focus, but still within the discipline of probability, they fall apart, with the disconsolate expression of an academic rat facing a professional hitman from organized crime.”

P. 284, Book IV

When asked for a rule about what to read: “As much as possible, the least of what was written in the last twenty years, except history books that aren’t about the last fifty years.”

P. 383, Book VI

“A half-man (or better, a half-person) is not someone who has no opinion; it’s just someone who doesn’t take risks for their opinion.”

P. 438, Book VII

“A lesson I learned from this ancestral culture was the notion of megalopsychia (a term expressed in Aristotle’s ethics), a sense of grandeur that was supplanted by the Christian value of ‘humility’. There is no word for this kind of magnanimity in Romance languages; in Arabic, it is called shhm—for which the best translation is ‘not small.’ If an individual takes risks and faces his fate with dignity, nothing he can do can make him small; if you don’t take risks, there’s nothing you can do to make yourself great, nothing. And when you take risks, insults from half-men (small men, those who don’t risk anything) are like barks from non-human animals: you can’t feel offended by a dog.”

P. 438, Book VII

“Verba volent, words fly. At no other time in history have people who talk a lot and do nothing been so visible and played such an important role as in modern times. This is a product of modernism and the division of tasks.”

P. 446, Book VII

“Think a bit deeper: the more complex the regulation, the more bureaucratic the network, and the more a regulator who knows the system’s loopholes and flaws will benefit from it later, since his advantage as a regulator would be a convex function of his differential knowledge.”

P. 477, Book VII

“First, the more complicated the regulation, the more prone it is to be arbitraged by people with privileged information. This is another argument in favor of heuristics. A regulation with 2300 pages—something that could be replaced by the Code of Hammurabi—will be a goldmine for ex-regulators. The incentive for a regulator is to rely on intricate legislation. Once again, those with confidential information are enemies of the less-is-more rule.”

P. 478, Book VII

“Distributed randomness (as opposed to the concentrated type) is a necessity, not an option: everything that is large has low volatility. And everything that is fast too. Large and fast are abominations. Modern times don’t like volatility.

And the Triad gives us some clue about what should be done to live in a world whose charm comes from our inability to truly understand it.”

P. 488, Book VII

💬 Enjoyed the article? Leave a comment and share your opinion!